Monreale

Monreale

The cathedral in Monreale, dedicated to the Virgin, witnessed the coronation and marriage of William II and served as the burial site for Sicily’s Norman rulers. Although it was a monumental project in terms of both architecture and decorations, subsequent donations and privileges swiftly made this monastic community one of the wealthiest in the Norman kingdom.

Documentary evidence dates the royal construction project to 1174, although initiatives in planning and preparation can be projected back to the death of King William I in 1166. Early documentary sources include the subordination and transfer in 1174 of the property from the cloister of Santa Maria di Maniace in the diocese of Messina, and a bull of Pope Alexander III confirming this transaction. Another bull confers privileges on the royal cloister’s abbot, which placed him directly under the authority of the pope, permitted him to wear the bishop’s insignia, and allowed him to convene synods. From these documents it is clear that construction was already underway in 1174. On January 15, 1175, moreover, the pope confirmed these privileges with a new bull, although this time with an amendment conferring on William II, as king, the right to confirm or reject the election of the abbot. Monks from Santa Trinità di Cava dei Tirreni, a Cluniac abbey north of Salerno, were summoned in the spring of 1175. Subsequently, about one hundred monks, led by the future abbot of Monreale, Fra Theobaldus, arrived a year later on March 20/21, 1176. The two monasteries maintained their relationship from that point on, and the visit of a delegation from Cava in 1177/1178 appears to be further indication that the construction of the church and cloister was likely already completed by that time. On August 15, 1176, the feast of the Assumption of the Virgin, the church was dedicated “Virgo Dei Genetrix Maria.”

The accounts of King William II’s marriage to the eleven-year-old Joanna of England on February 13, 1177 in the chapel of the royal palace in Palermo suggest that the festivities took place in the Cappella Palatina. Archbishop of Salerno, Romould Guarna, reported, however, that large crowds arrived to witness the marriage and coronation, which would be inconsistent with the relatively small interior of the Cappella Palatina in Palermo. It is, therefore, much more likely that both the marriage and the coronation took place in the cathedral in Monreale. In the marriage certificate the recently elected abbot Theobaldus of Monreale describes himself as “Ego theobalduns episcopus, abbas regalis monsterii Sanctae Maria Nove.”

Already one of the wealthiest monasteries in the Norman kingdom by the time of the marriage in 1177, it now stood as the burial site of the Norman kings as well. Already in 1174 William II had transferred to Monreale the mortal remains of his father, King William I. He did the same with those of his brother and, in 1183, also interred his mother, Margaret of Navarre.

Pope Lucius III eventually elevated Monreale officially to the status of cathedral on February 5, 1183 and named the new archbishopric “Mons regalis.” Another date is provided by the delivery, in 1185, of bronze doors from Trani and Pisa for the cathedral’s entrance, which indicates the terminus ante quem for the building’s completion.

Based on the preceding evidence, especially the arrival of the bronze doors, and the traditional assumption that the capitals of the cloister were coterminous with those of the church, the cloister sculptural program would have been finished in an incredibly few short years.

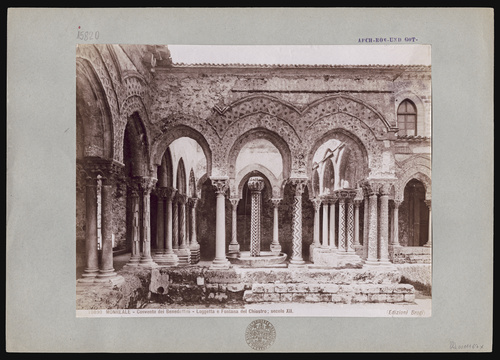

Of the former Benedictine monastery complex and the affiliated royal palace, only the cloister remains intact today, situated next to the cathedral and a few associated ruins. It is attached to the south side of the church and derives its measurements (47 x 47 meters) from the length of the nave. Each of the square cloister’s four sides consists of arcades with pointed arches whose double columns stand on a low support wall (68 cm) that is periodically cut away to form entranceways. At the southwest corner of the complex stands a fountain-house; its center marked by a column that performs the function of the fountain. The chapter house was originally located on the east side of the cloister, the dormitory on the south side, and the refectory on the west. The severe rhythm of the cloister arcade is softened in so far as the column shafts are either decorated with relief sculpture (as in the case of the corner columns), inlaid with colored stones, or else alternately plain. Each gallery contains 26 double columns and has a cluster of four relief columns at each corner.

Double bases rest on a common plinth and support the twin columns, which correspond to the way columns themselves are crowned with monolithic double capitals, the latter being capped by a single impost block that unites them. It should be noticed as well that the lower section of the capitals is for the most part wrapped in a decorative fringe of acanthus or leaves, which serve as a base or background for the carved figures. Consequently, the capitals’ basic form varies little and usually takes the form of an inverted cone, exhibiting elements of either Corinthian or composite styles.

The cloister’s regular decorative scheme stands in contrast to the richness and variation of its sculptural ornamentation. Of the 104 double capitals and 5 quadruple capitals, 15 are historiated and depict biblical subjects, with a preference for the New Testament over the Old. Representational schemes that are common to cloisters in general include the apostles, stories from the infancy of Christ, the Resurrection, John the Baptist, and the parable of Lazarus. From the Old Testament, common narratives include episodes from Adam and Eve, Noah, and the stories of Jacob, Joseph, and Samson.

Apart from ornamental foliated capitals, there are numerous figurative capitals of profane or mythological character that depict allegories, hagiographies, the dedication of the cathedral to Maria, and the Christ Child. On the whole, the individual scenes do not seem to comprise a unified program. Rather, they confine themselves to each set of double or quadruple capitals without establishing any direct connections across adjacent columns.

With respect to the figurative and narrative scenes in particular, the decoration is clearly not limited to the capital itself, but often breaks through the level of the abacus and projects into the impost block. Both abacus and impost block are occasionally inscribed with explanatory inscriptions, arabesques or smaller figures. Nor is the figurative or narrative decoration confined to one of the twin capitals; instead it frequently extends itself - especially in the case of narrative scenes - across both capitals, thereby binding the double columns into a single organized unit.

The authorship of highly-experienced stone cutters and artists can be seen in the deeply carved and the extensive deployment of elements in high relief, in the slender figures and exacting attention paid to the details of their clothing and facial expressions, in the rich variation of bodily movement in lively scenes, and not least in the masterful use of the running drill.

Different workshops likely hailed from southern as well as northern Italy and southern France. Some of them owed their artistic language to classicizing and Byzantine production of ivories and mosaics. This stylistic variety, however, is subordinate to the clear spatial logic of the cloister’s pre-existing proportions. The capitals were carved from white marble, but over time has acquired a thick, sandstone patina that covers them almost entirely, which only becomes apparent in places that have been cleaned in successive restorations or have suffered damage by chipping. Material nalysis reveals that the stone is likely parian marble from Greece, which was readily available from numerous ancient Greek ruins in Sicily.

The Cloister of Monreale – Imaging Plan and Reproduction of the Capitals

All capitals were photographed from four sides

(north, south, west, east).

31 capitals were photographed from eight sides (N, S, W, E, NW, NE, SE, SW). The symbols N, S, W, E stand for the directions north, south, west, east.

The images were sequentially ordered according to the numbering of Salvini 1962 and Sheppard 1949.

E.g., N8Sh7N

N8 is the number in Salvini 1962, who numbered each side of the cloister from 1-26.

Sh7 is the number in Sheppard 1949, who numbered the capitals in order of their arrangement from 1-100. He indicated the corner capitals with their directions, e.g., NE for northeast.

The capitals around the well in the southwest are denoted with L, e.g., L1, L2, etc. N stands for the side (north) from which the capital was photographed. If it had been photographed from the south, for example, the number would be N8Sh7S.

Bibliographical reference

Salvini 1962 Salvini. Roberto: Il chiostro di Monreale e la scultura romanica in Sicilia, Palermo 1962

Sheppard 1949 Sheppard, Carl D.:

Iconography of the cloister of Monreale. In: The Art Bulletin, 31.1949 No. 3, p. 159-169

Dittelbach 2003 Dittelbach, Thomas: Rex imago Christi - der Dom von Monreale. Bildsprachen und Zeremoniell in Mosaikkunst und Architektur, Wiesbaden 2003

Ghigo Roli, 2019